In October 1949, Dorothy Emmet, Manchester University’s Professor of Philosophy, pulled together a seminar, Mind and the Computing Machine to grapple with Alan Turing’s claims that computers were going to think. As I discuss in my book, they didn’t make that much progress, though the obtuseness of one of the participants may well have provoked Turing to write the now famous Mind paper in which he introduced the Turing Test.

We know a fair bit about the content of the seminar, because a transcript survived, but we don’t really know much about why it happened and, in particular, what effect it had. One of those present was a young philosophy lecturer named Wolfe Mays and, probably his equally new colleague Desmond Henry; his daughter Elaine O’Hanrahan has assembled some evidence on how Turing’s lack of a philosophy of consciousness was received in the Philosophy department (spoiler: not that well).

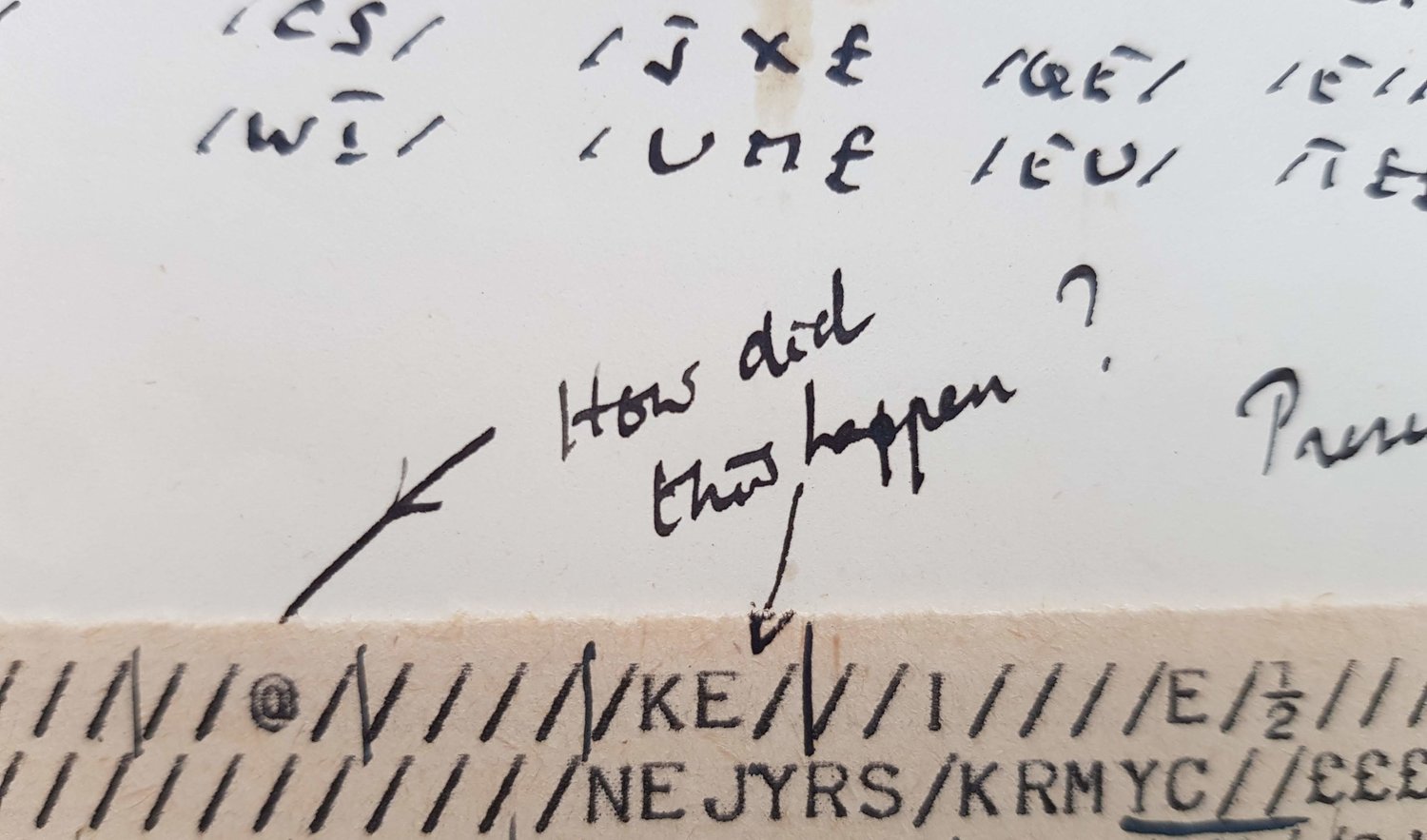

But this post is triggered by finding a piece of evidence that the participants kept the discussion up at least one more time. It comes from J Yule Bogue, an American running the ICI drugs division which had just moved to Wilmslow, and who briefly appears in my book as Max Newman’s more interesting neighbour, and it is a note to the great American neurologist/poet/cybernetician (not that great as a poet, perhaps) Warren McCullough at MIT about an ‘amusing evening’ on minds and machines.

I wish you had been with us a few days ago we had an amusing evening discussion with Thuring [sic], Wiliams, Max Newman, Polanyi, Jefferson, JZ Young & myself. An electronic analyser and a digital computer (universal type) might have sorted the arguments out a bit.

McCulloch himself had no ‘universal machine’ under construction himself, but he and his (then-)colleague Norbert Wiener were at the heart of the US Macy conferences which were struggling with the same questions as the Manchester seminar, if on a grander scale and more successfully. Interestingly the note shows that the creator of the Mark I, FC Williams, who had either been excluded from Emmet’s discussion or chosen not to go, was included this time, though Kilburn and Emmet aren’t mentioned.

There is a copy of the note in the American Philosophical Society Warren McCulloch archives.