Festival of Britain publicity shot in front of the temporary facade of the Lower Campsfield Market, now the Air and Space Hall of the Museum of Science and Industry.

The 1951 Festival of Britain showed Britain to itself as what Christopher Frayling memorably described as a place of ‘atoms and whimsy’ and has been heavily quarried now as a source of social history. For all its fascination I had assumed the Festival was too London-centric to use for my purposes. But I was wrong on two counts - firstly that Turing and a good few other Mancunians went to it in London, and secondly, that, to my surprise, the Festival came to Manchester. This post is about that Manchester end.

Those who could not visit London were not forgotten as consumers of the Festival. There was a Land Travelling Exhibition, ‘the largest ever’, that spent a few weeks in what is now the Air and Space hall of the Museum of Science and Industry. It later visited a half-dozen other cities, but with a budget of £200K it was never on the same scale as the South Bank which had £6m spent on it.

The Victorian glass and ironwork frontage, now so proudly presented to Liverpool Road, was hidden under a temporary, modernist facade, and at night twenty-one red, white and blue ex-navy searchlights marked the sky above Deansgate. The Manchester Guardian sent Norman Shrapnel, who responded in a characteristic Mancunian tone, both appreciating the cosmopolitan elegance and being perversely unwilling to be bowed by it:

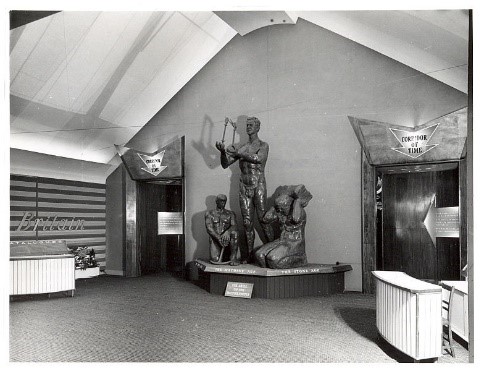

‘It is informative, imaginative, and always — excessively, some people may feel — elegant. Much of this show could call itself a Festival of Stockholm or of New York and the Manchester visitor may excusably decide that it is magnificent but it is not home. It is the cosmopolitan poker face that tires in the end. The bite of what is characteristically national (let alone regional) is to be found only here and there; one becomes exasperated and insular, hugging one’s vices and wanting to look through the draped false roof at the surge of dirty glass above, or to gaze affectionately at the Albert Square statues. But this is perverse; the huge sculpture by Fiore de Henriquez in the foyer, is (in all senses) a cut above Gladstone or John Bright’.

de Henriquez’ sculpture, The Skill of the British People, greeting visitors to the Festival.

Fortunately the Sunday Pictorial weren’t paying attention to the huge de Henriquez piece. de Henriquez had been brought up and lived largely as a woman, but considered herself a hermaphrodite (actually, she thought everyone was a hermaphrodite, but that in her own case it was particularly visible) and later would have to put up with the press insisting she be photographed smoking cigars, but the 1951 Festival-goer was innocent of all this. In the 1960s de Henriquez underwent castration by radiotherapy, although unlike Turing’s treatment a decade earlier, this was a voluntary decision.

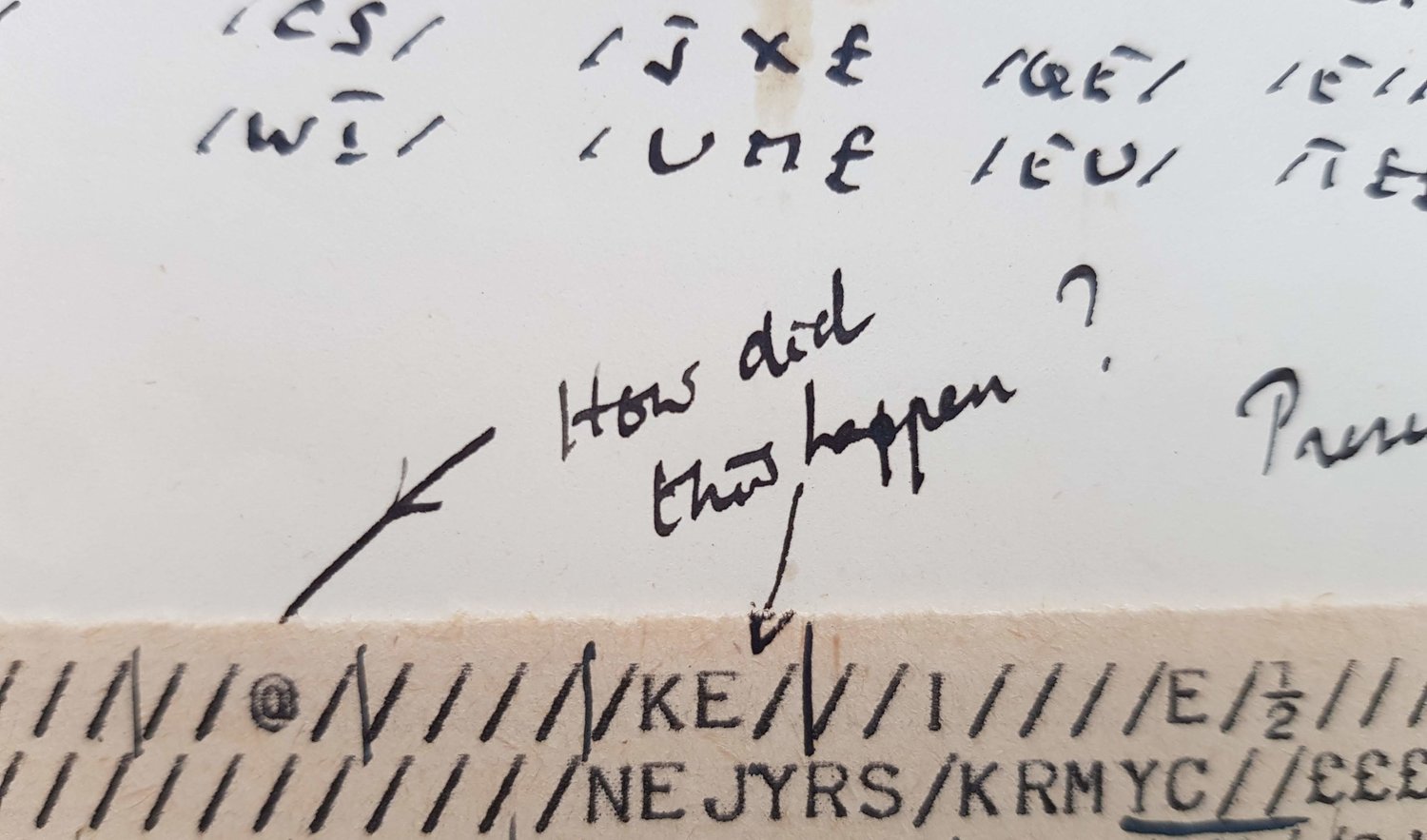

The Manchester Guardian acknowledged that the best of contemporary world culture, like de Henriquez’s un-perverse sculpture, was accessible enough to be appreciated and admired but was sceptical about whether visitors could connect it with their own more mundane lives. It was only when the rough edges peeped through that Shrapnel felt engaged. He went on press day, which meant that

‘nothing was finished. Men with brooms, like lost souls, were plodding up and down the Corridor of Time — an exciting dream-like construction with great pendulums swinging overhead. You pass from there into a section which shows something of what two centuries of science have done for us all, and into that devoted to People (“some people,” might be the wryly justifiable comment) At Home. Plainly, it would all be charming when it was finished. Meanwhile queer notices lay about the place. “Do not mislay Adam stove handle,” said one. Realism was caught here in the period of British Hortatory’.

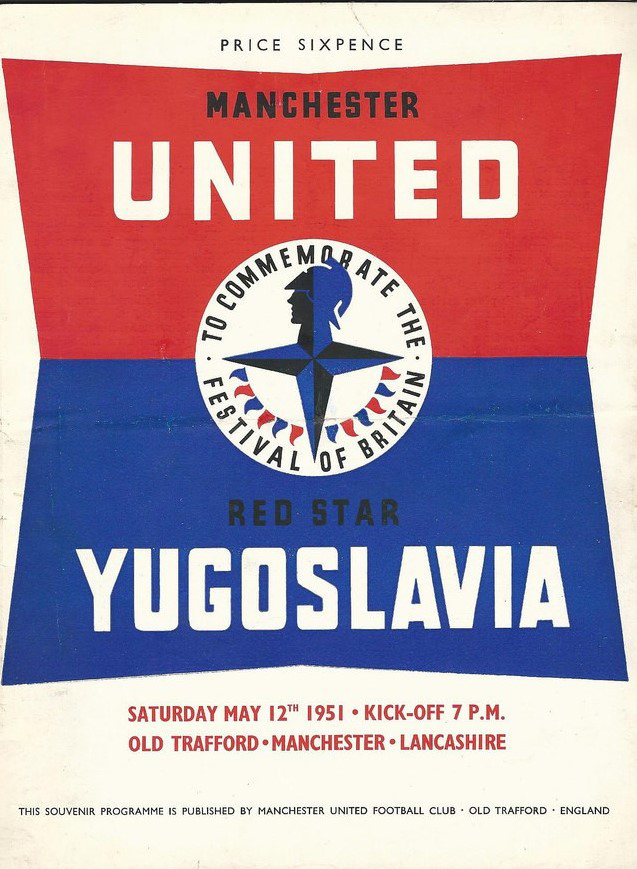

And that was that. Manchester’s response was relatively subdued and ticket sales were disappointing. After a few weeks, the sixty-foot pantechnicons moved on to Birmingham. There wasn’t much else save some sporting events that would probably have happened anyway. As well as a match against Red Star Yugoslavia, Manchester United also travelled to Stretford Gas Social Club to play a Festival of Britain Grand Football Match against a team from Sale. To my knowledge, there are now no physical relics of the Festival left in Manchester, save at Hyde Town Hall where there is a large and overconfident mural ‘painted for the Festival of Britain’ but surely not with the consent of the Festival Design Group.