It’s well known (thanks as usual to Andrew Hodges) that Alan Turing did not shy from public view whilst awaiting trial as a sex offender. The day after his arrest, Turing went to London for the February 1952 meeting of the Ratio Club; the day the newspapers reported the first hearing he debated with the high profile chemist Prigogine on a visit to Manchester. What I hadn’t known until now was that in the very week after Turing was found guilty and sentenced, he had arranged to give a talk at the Manchester meeting of the Society for Experimental Biology.

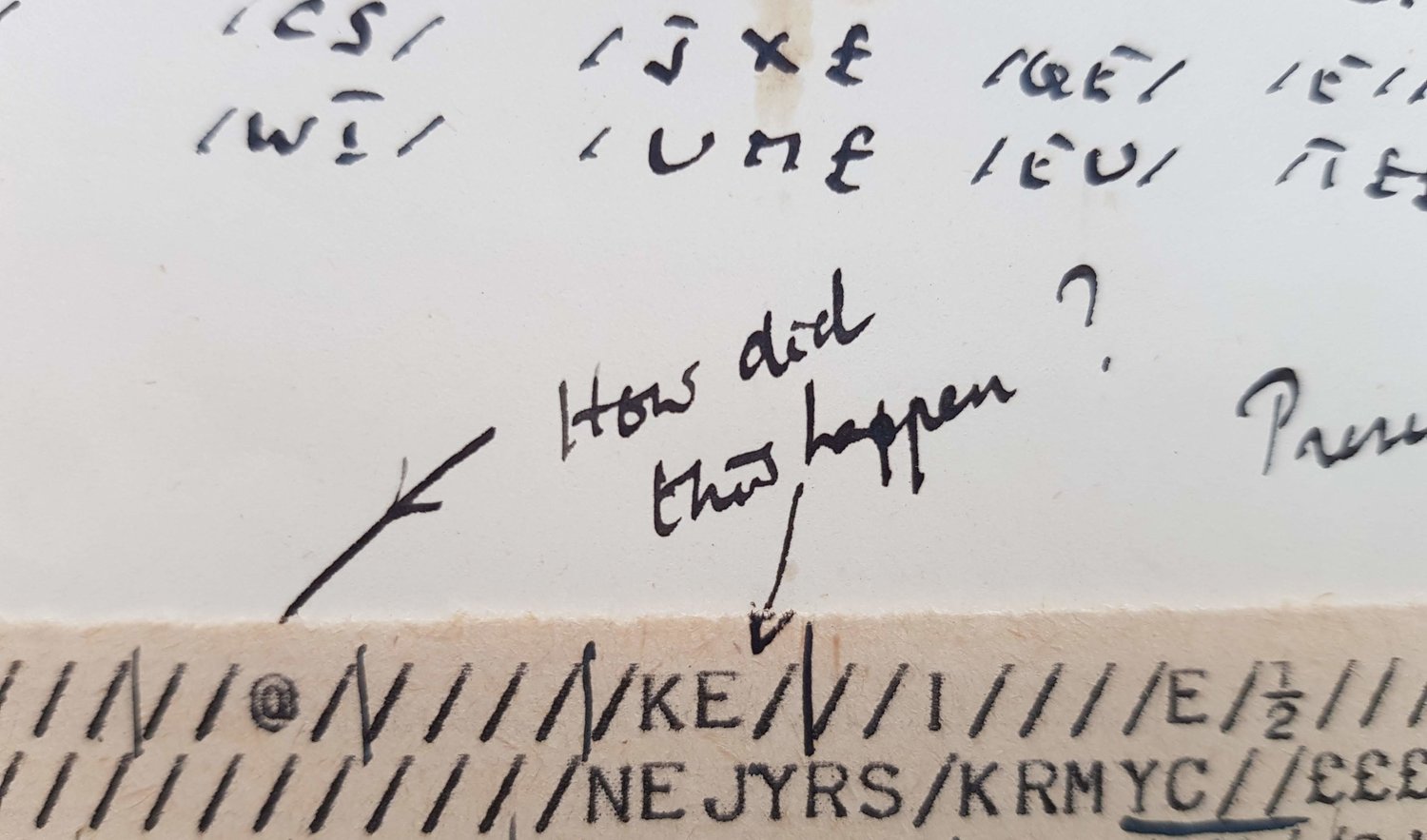

Society for Experimental Biology Manchester meeting programme, 1952, thanks to the SEB archivists for locating and providing this.

I don’t know if Turing turned up to give his talk: given his track record and the enormous importance of the morphogenesis work to him he probably did. What he talked about was almost certainly the paper he had submitted the previous November to Proceedings of the Royal Society. Nobody seems to have remembered the talk particularly: the one developmental biologist who was most enthused by Turing was Claude Wardlaw who already knew of the work (and likely had a hand in getting Turing on the programme). In hindsight, the Snow’s experimental program fitted very well with Turing’s theoretical one but there is no record of any personal connection ever being established. The chair, Joseph Woodger, was a remnant of an earlier and largely failed attempt at theoretical biology. It is very unlikely that Turing would have failed to read Woodger’s 1937 The Axiomatic Method in Biology (1937). Woodger’s book was a forlorn attempt to transfer the Russell-Whitehead logical calculus of Principia Mathematica to a finite list of biological facts (in practice just Mendelian genetics, though not even that is fully worked out), and Turing would have surely have understood that this process jettisoned all the interesting phenomena and paradoxes of infinite logical systems. Unusually for a trained logician, Turing was also demonstrating himself as a skilled applied mathematical modeller: he could not have failed to see that Woodger was not. So I rather doubt Turing found much of interest in him. On the other hand, at about this time Turing made a lifelong friend in Joseph Woodger’s son Michael.