There is an image of the Turing family spoon at this link. But here is a picture of a different one, because photographs of spoons are copyright, to encourage innovation in spoon photography, and when publicly funded museums take pictures of spoons they give them to paid media outlets, but don’t release the publicly funded photograph under any kind of free license, even though that means they don’t get a link back to their exhibition.

Among the books and manuscripts preserved by the Modern Archives at King’s College Cambridge, one of the more simultaneously innocent and gruesome artefacts is one of Alan Turing’s teaspoons. It’s not very striking: I’m not even sure if I’ve seen it or not. It’s a carefully catalogued spoon.

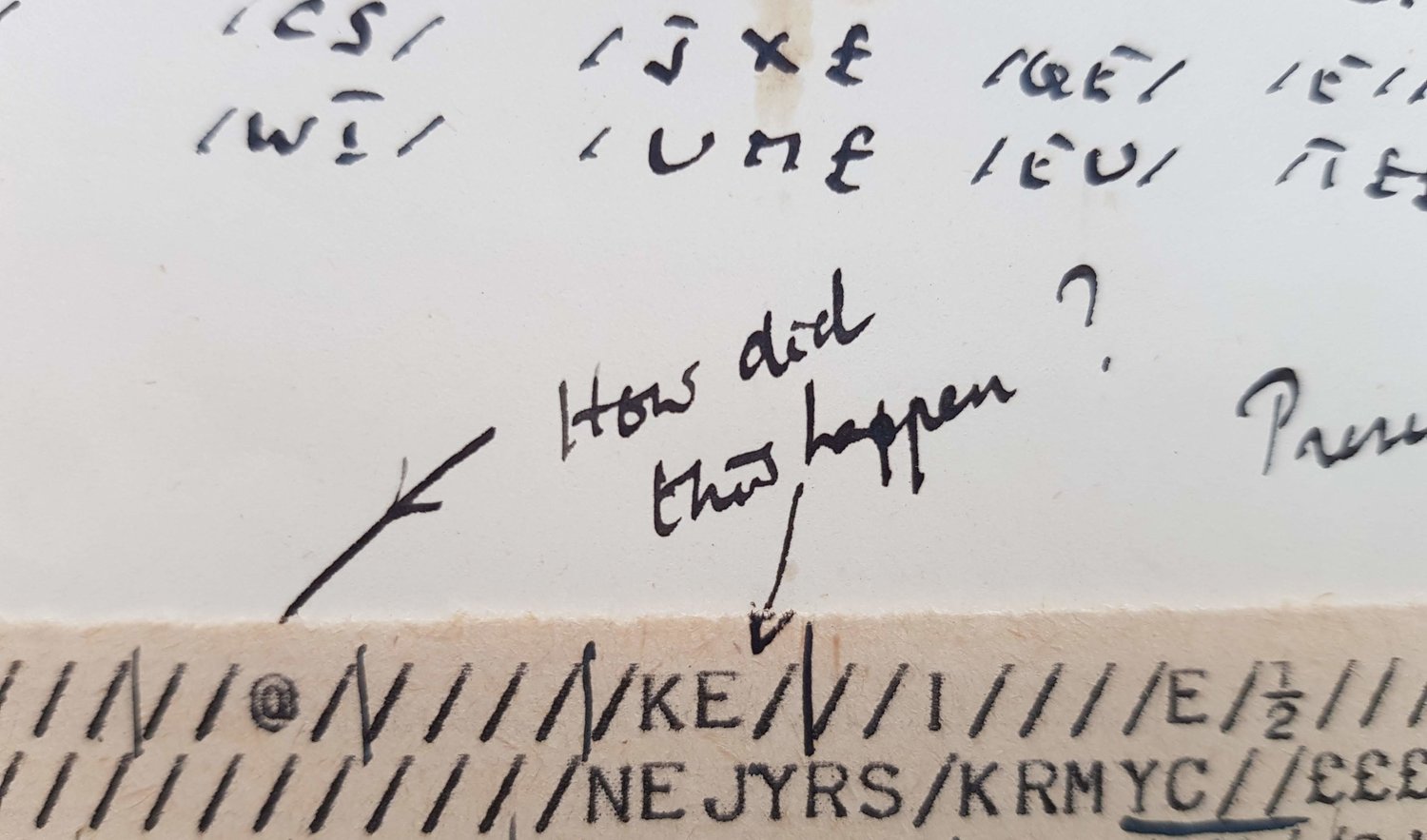

It’s just a spoon, and yet it carries much more freight than a random possession. His mother, Sara Turing wrote that she found it in Wilmslow “in Alan Turing's laboratory. It is similar to the one which he gold-plated himself. It seems quite probable he was intending to gold-plate this one using cyanide of potassium of his own manufacture”. So not the actual spoon of death, nor a gold-plated one. But nevertheless it carries a painful reminder of the souls we (ok, I) dabble in when we try to read and write history. Andrew Hodges has long suggested, with cogent evidence, that Alan Turing had carefully devised a suicide scheme that would avoid over-distressing his mother by allowing her to believe that an accident has occurred. Whatever happened, Sara did indeed always maintain that her son’s death was an accident, and including the spoon with the other papers (whose significance she was convinced of, although no-one could understand most of them) she donated to King’s was part of that position.

So the spoon, with neither gold nor cyanide upon it, sits in King’s because Alan Turing’s mother saw it as a saintly icon. It turned out she was right, but Sara was not to know that the absent-minded genius she would portray in her 1959 biography of her son would have to be replaced by the martyr genius shown by Andrew Hodges in 1983 before Turing’s actual canonisation could proceed.

It’s not the only object acquiring power by association with Turing. There’s no greater example than Google being persuaded to cough up half a million quid to Bletchley Park for the utterly uninteresting (and, Daily Telegraph, utterly unsecret) set of Turing offprints that someone successfully flogged them.

(There’s no picture of the spoon here for copyright reasons but here is a link to the picture at The Guardian; as usual references are available in my book Alan Turing Manchester).