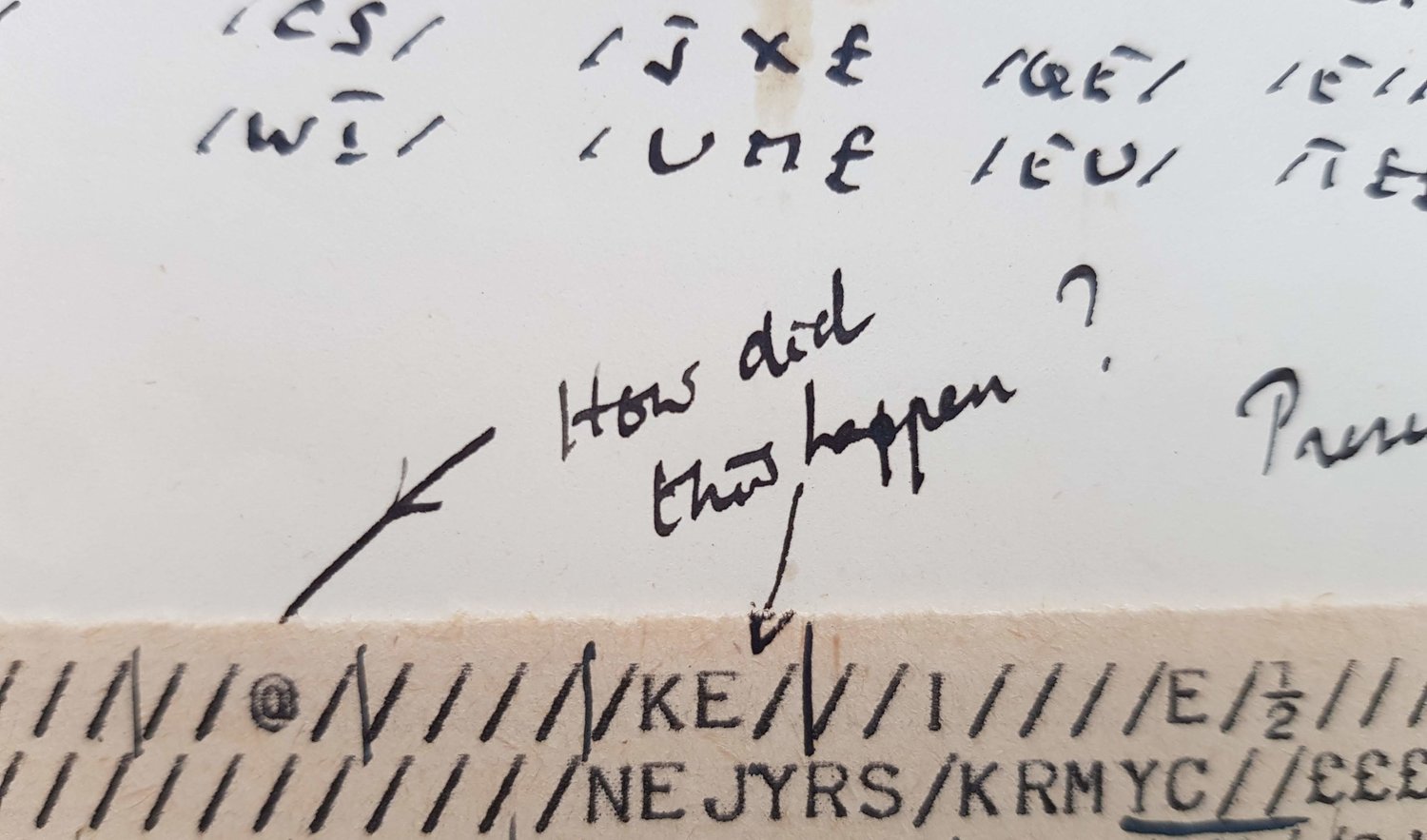

It has been literally hiding in plain sight. After Turing’s death, his mother Sara received a number of letters of condolence, which she later made use of in her biography of her son. One of these letters was from Conel Hugh O'Donel Alexander, who had been at King’s three years before Turing, and got to know him well when they both worked at Bletchley Park. The letter is a moving and authentic one, written by a man who knew his friend well, telling Sara of her son’s ‘power to win the affection of everyone who really knew him’ and Alexander’s admiration of his ‘profound originality and insight but for his simplicity and honesty’. Sara Turing donated the first page of the letter to King’s, along with (presumably) most of the other material she had used in the preparation of the biography, some time before her death in 1976. It has been there, available to scholars ever since. But as the image shows, Mrs Turing painstakingly redacted the address and one of the paragraphs.

And this is where an astonishing thing happened a few years ago. The imaging unit of the University Library in Cambridge has been developing multispectral imaging and CT scanning to image manuscripts: they recently showed off their ‘modern magic’ by unlocking Merlin's medieval secrets. Back in 2020. decades after Andrew Hodges had interviewed his witnesses and wrote his book and read the redacted latter, the UL team tried this new technology on the Alexander letter. And it worked: here is the text they found under Sara Turing’s redaction:

he would be asked if he admitted that what he was done was really wrong. Rightly or wrongly he himself did not think he had done wrong and that being so he himself would rather have been imprisoned than admit to it ; and it wasn’t obstinacy, he just would not have lied in order to escape. (King’s College Cambridge AMT A/17)

There’s a sadness in his mother’s need to censor this material in order to do what was right in her mind by her son, but that is another story. The revealed image was shown in an exhibition at King’s, but perhaps because of the pandemic this amazing recovery seems not to have attracted any PR flacks or made its way into the world wide web of Turing narratives. So it seems worth posting here: it is why, despite some initial scepticism I do in the end accept that Simon Goldhill got the big call right. (On the ‘political clarity’ of Turing’s personality that is; I’m still wary of the value claim that attributes Turing’s character to King’s culture).

Neither I nor (I think) Simon Goldhill had anything to do with deciphering the Alexander letter and I’m grateful for the cooperation of the Modern Archivists at King’s for explaining it. I’m especially grateful to Andrew Hodges not just for telling me about the decipherment in the first place, but for positively engaging with a previous and badly wrong version of this post. Both the image of the redacted first page of the letter and the quotations from it are copyright by the estate of CHO’D Aexander. I think my use of them is fair use but I’d be grateful to hear from any copyright owner. I’ve not reproduced the unredacted image as I assume the UL own some copyright in it, but a paper copy of it is held at King’s A/17 too. It is from there I have taken the ‘he would be asked’… quote after ignoring some words I can’t make out. I don’t know any technical details of the imaging itself or who carried it out and I would love to hear from anyone who does.

Some other myths

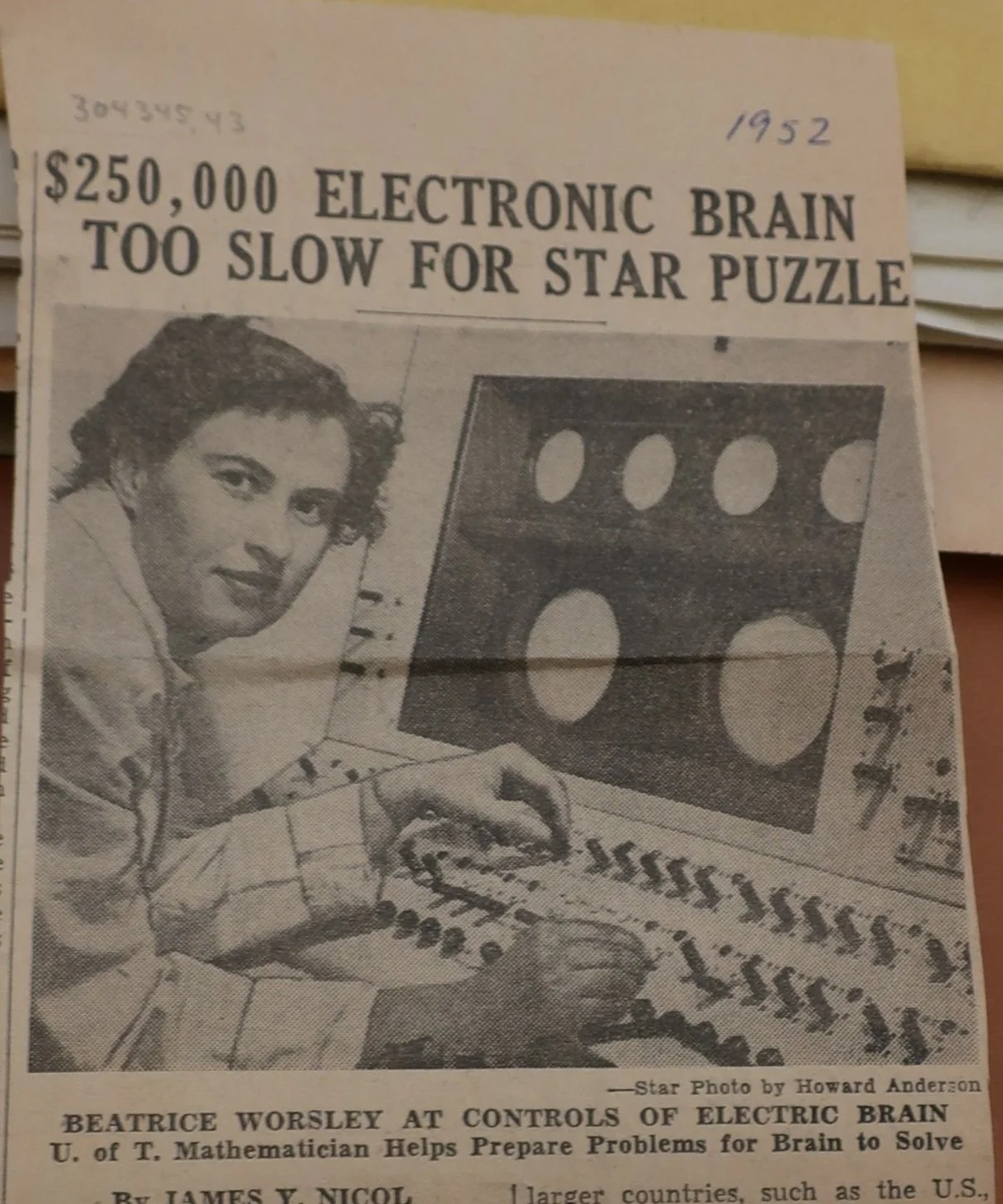

While we’re here, some factual comments on Queer Cambridge in an attempt to keep other myths vaguely anchored to historical evidence. Alan Turing was never ‘living with’ Arnold Murray, the 19 year old he was co-charged with for gross indecency. The only positive evidence we have is Murray’s account thirty years later to Andrew Hodges that Murray had been picked up by Turing on Manchester’s Oxford Road in November 1951 and stayed overnight at Turing’s house in Wilmslow a few times between then and their arrest in February 1952. Turing’s long-term relationships were entirely within his own upper-middle class.

It also seems worthwhile to me to try and be clear about what it means to say that the justice system ‘offered the choice’ to Turing between prison and chemical castration. Here there’s no new evidence: most of what follows is direct from Hodges. There was certainly a question to be asked about whether a man guilty of a crime should be punished or treated, but there was no clear idea in court as to what would be appropriate treatment. This vacuum was partly being filled by oestrogen therapy, being publicised in the UK at the time for

the ease with which it can be administered to a consenting patient we believe that it should be adopted whenever possible in male cases of abnormal and uncontrollable sexual urge. (Golla and Sessions Hodge, ‘Hormone Treatment of the Sexual Offender’, The Lancet, 11 June 1949, via Hodges).

Beyond the Lancet paper, I don’t know of any other archive material that tells us what the medical and legal professions thought of hormone treatment if at all. But if the judge was aware of this emerging option, he chose not to stipulate it. The choice the judge offered was between prison and probation, with a condition of that probation being simply if inexactly that he ‘submitted’ to the care of a ‘registered medical practioner’ at the Manchester Royal Infirmary. (Dermot Turing’s Prof is one useful additional source here). Yet between the 1949 paper and the 1952 hospital appointment, Golla’s published insistence on ‘consent’, without which he would have drawn considerable criticism from his own profession, had in the hands of the MRI ‘practitioner’ become ‘obligation’: a couple of weeks later, Turing wrote to a Cambridge friend

I am both bound over for a year and obliged to take this organo-therapy for the same period. It is supposed to reduce sexual urge whilst it goes on, but one is supposed to return to normal when it is over. I hope they’re right. The psychiatrists seemed to think it useless to try and do any psychotherapy. (Turing to Hall 17 Apr 1952 quoted in Hodges)

For the first nine months, Turing was prescribed and took oestrogen pills. Then came a resonant switch: for the final three months the oestrogen was delivered from a subcutaneous implant. We know this, because when the probation year was up Turing very promptly had it removed. (This evidence rests primarily on the memory of, probably, Robin Gandy). No doubt there was an objective, phamacological rationale for the switch, but it might also be seen as an internalisation of coercion by those who know Foucault.

This is not a review of the whole Queer Cambridge. The title is absurd and excluding, like calling a monograph on EM Forster novels Queer Literature. But there’s much to like in the warmth with which Simon Goldhill retells, and re-creates, King’s creation myth of an intellectually or aesthetically rigorous but socially tolerant society. I learned a lot, mostly not very interesting to those not interested in King’s self-mythologising but fascinating to those like me who are. I would have been more comfortable enjoying the book if Goldhill had extended the tolerance and empathy he celebrates to the victims of the snobbishness and misogyny he cannot ignore but notes only in passing. Perhaps it was indeed impossible to look for testimonies from the series of male sex workers who have apparently trooped into the Gibbs building over the decades. But negative evidence of the culture Goldhill’s subjects bequeathed has been there to hear at his own High Table over the years. In my experience , for example, it doesn’t take much prompting of women with experience of that academic culture to yield other, less glowing perspectives of how those values impacted on them.